5 Reasons why EC’s reply to Rahul Gandhi raises only questions, not answers

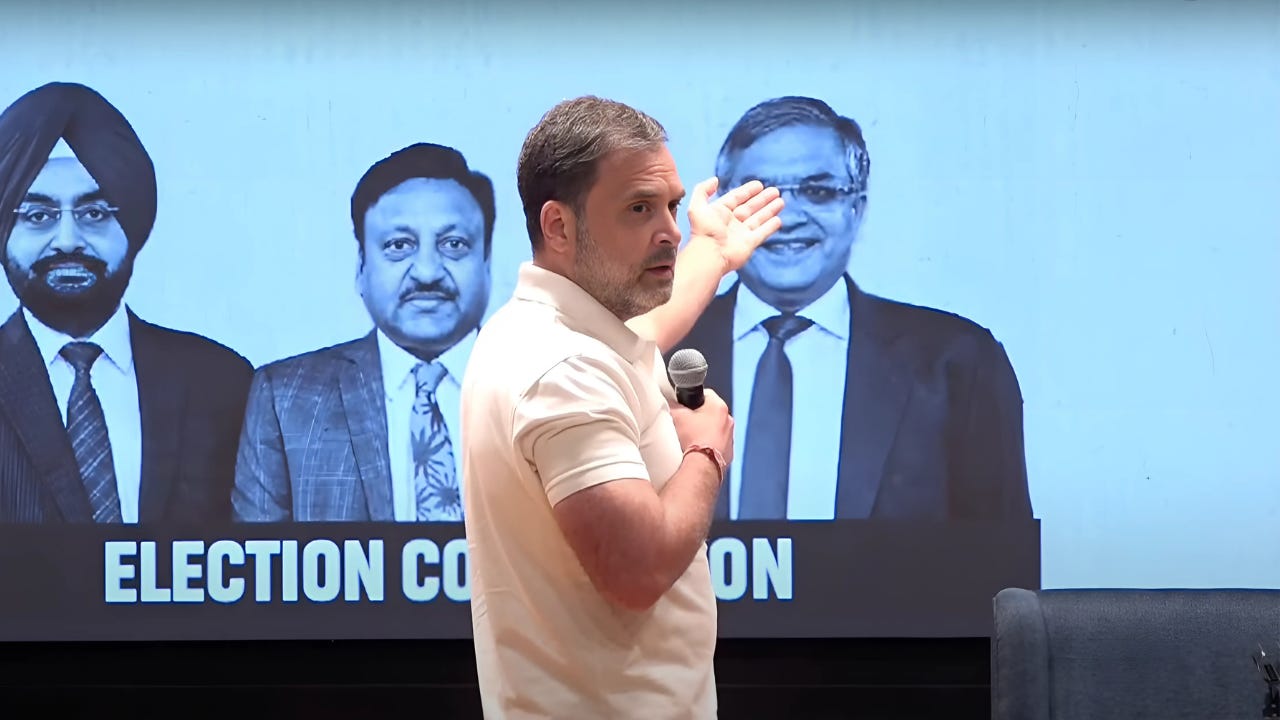

The Election Commission’s reply to Rahul Gandhi prompts scrutiny — not only for what it said, but when it said it

By Sanjay Dubey

1. Reply out of turn

The Election Commission’s first public reaction to Rahul Gandhi’s press conference (PC) was notable as much for its timing as for its content. Gandhi was still midway through his 70-minute briefing — having just finished the main part — when the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) of Karnataka posted a letter in response to his allegations on social media. Shortly afterwards, similar statements came from the CEOs of Haryana and Maharashtra, all quickly echoed by the EC’s own official account.

The speed alone suggests this could not have been a considered reply to Gandhi’s detailed allegations. The content reinforced that impression. For example, at one place it states, “It is understood that during a Press Conference held today, you had mentioned about the inclusion of ineligible electors and exclusion of eligible electors in the Electoral Rolls…”

This is factually incorrect. Had the EC listened carefully before writing its response — or simply waited until Gandhi finished — it likely would not have done that. In the later part of his briefing, Rahul specifically mentioned,“we have only shown voter addition (inclusion of ineligible electors). There is also something called voter subtraction (exclusion of eligible electors). We know that it is almost of the same scale, but, we haven’t got the data to assert that, so, we are not talking about.”

Rather than engaging with the core issues or showing any intent to address them, the EC’s response clearly looks like what it likely was — a hastily drafted, centrally co-ordinated standard bureaucratic note, leaning on unnecessary technicalities. The urgency seemed less about fact-finding and more about seizing control of the narrative before it could take shape in the public mind.

2. Technicality as tactic

The Karnataka CEO’s letter invited Gandhi to submit his allegations via a sworn affidavit under Rule 20(3)(b) of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960. On paper, this might seem like a legitimate step. In practice, as senior advocate Kapil Sibal has pointed out, it is a procedural cul-de-sac.

Rules 12 to 20 cover claims and objections for the inclusion and exclusion of names in and from the electoral rolls. Rule 12 imposes a 30-day limit from the draft’s publication for lodging claims and objections. And Rule 17 mandates that any claim or objection filed after this period “shall be rejected”. Rule 20 simply prescribes how such claims and objections are to be filed and examined.

In this case, the 2024 electoral rolls had been finalised months before Gandhi’s 7 August 2025 press conference. That makes Rule 20(3)(b) inapplicable even for a single claim or objection, let alone post-poll systemic fraud allegations by the Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha. Even if Gandhi complied, the EC could reject it outright under Rule 17 as “out of time”.

3. Discretion as weapon

The affidavit format attached to the Karnataka CEO’s letter requires Gandhi to list, for each disputed voter, the name, the part number of the electoral roll, and the serial number in that roll.

Considering Gandhi’s allegation of over 1,00,000 suspicious entries in Mahadevapura, meeting this demand would require manually recording each detail — a bureaucratic marathon bordering on the absurd.

And this is not only inapplicable here but also legally unnecessary. Rule 20(3)(b) says that “The registration officer may in his discretion require that the evidence tendered by any person shall be given on oath and administer an oath for the purpose.” The four words — “may in his discretion” — make clear the affidavit is an optional requirement, not a legal necessity. The EC could just as well accept a simple paper submission.

Section 31 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 criminalises false declarations on electoral rolls. Section 227 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Samhita, 2023 also does the same. This means even a tiny percentage of clerical errors — inevitable at this scale — could expose Gandhi to criminal prosecution. As former CEC O.P. Rawat noted, this could well be why the EC insisted on an oath in Gandhi’s case.

4. The lose-lose logic

The EC’s “invitation” to file an affidavit creates a façade of openness while boxing Gandhi into a lose-lose situation. If he filed, he risked legal jeopardy from inevitable mistakes, or dismissal of his complaint on the purely technical ground of being late. If he refused, the Commission could claim he was unwilling to lodge a “proper” complaint — painting him as someone making baseless allegations.

This framing was reinforced in the EC’s follow-up statements of 8 June 2025, which repeatedly argued that:

a) If Shri Rahul Gandhi believes in his analysis and in the truth of his allegations against election staff, he should have no objection to filing claims and objections against specific voters, and signing the Declaration/Oath under Rule 20(3)(b) of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960.

b) If Shri Rahul Gandhi refuses to sign the Declaration, it shows he does not believe in his own analysis or conclusions, and is making absurd allegations — in which case he should apologise to the nation.

5. Discretion over transparency

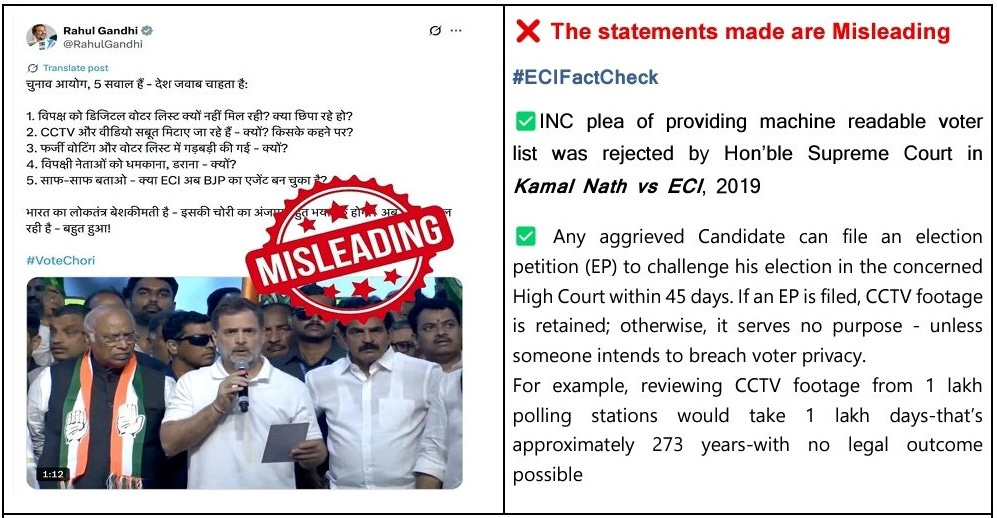

The EC also addressed Gandhi’s demand for a machine-readable voter list, bluntly stating that “INC plea of providing machine-readable voter list was rejected by Hon’ble Supreme Court in Kamal Nath vs ECI, 2019.”

This is technically correct — the Supreme Court upheld the EC’s refusal to provide such lists, citing privacy concerns — but the ruling only says the EC is not obliged to provide them. It does not forbid the Commission from doing so.

In other words, the decision remains entirely at the EC’s discretion, provided privacy safeguards are applied. The EC could retain image-PDFs for public display while granting controlled, audited machine-readable access to recognised parties or accredited auditors — with sensitive fields redacted, usage logged, and misuse penalised. That would protect privacy while ensuring transparency, if the EC chose to allow it.

Regarding Rahul’s demand for CCTV footage, the EC said in its response:

"Any aggrieved candidate can file an election petition (EP) to challenge his election in the concerned High Court within 45 days. If an EP is filed, CCTV footage is retained; otherwise, it serves no purpose — unless someone intends to breach voter privacy."

Then it adds something that again borders on the absurd:

"For example, reviewing CCTV footage from 1 lakh polling stations would take 1 lakh days — that’s approximately 273 years — with no legal outcome possible."

It is pertinent to note here that just after the Maharashtra elections, the Ministry of Law amended the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961 on the EC’s advice. This effectively shut the door on any attempt to inspect CCTV footage of polling booths. And in June 2025, the EC went a step further, instructing its officials to destroy CCTV, webcasting, and video footage of the election process after 45 days.